Calendars for babies, or, project management with AIs

This write up happens in two parts – a basic use case write up, and then a meandering set of conclusions and ideas at the end.

Basic instructions

1. Use case

Any new parent will understand the sheer amount of time one spends learning and thinking about baby schedules. The corpus of concepts is enormous: “wake windows”, “feed schedules”, and sleep techniques quickly permeate everything you do. Imagine dreaming about sleep schedules…

Anyway, as our baby’s gotten older, we spend less time diligently tracking everything he does in a vain attempt to understand him, and a bit more time steering him (and us) into target schedules. We found that the baby, when given structures he likes, responds well.

In particular, I like to track these in Google Calendar, but I spend an inordinate amount of time making and managing calendar invites.

2. Prompting

I asked Claude to help with the following:

You are an expert executive assistant engineer. You are going to help me manage my baby’s schedule. To start with, can you help with the following: 1. Make a CSV of the schedule based on the image attached that I can upload to Google Sheets, 2. Given a Google sheet ID, write code that can create calendar invites from the schedule that is written in the format you select Assume I’m using Google Calendar. I want the calendar events to recur daily for a week.

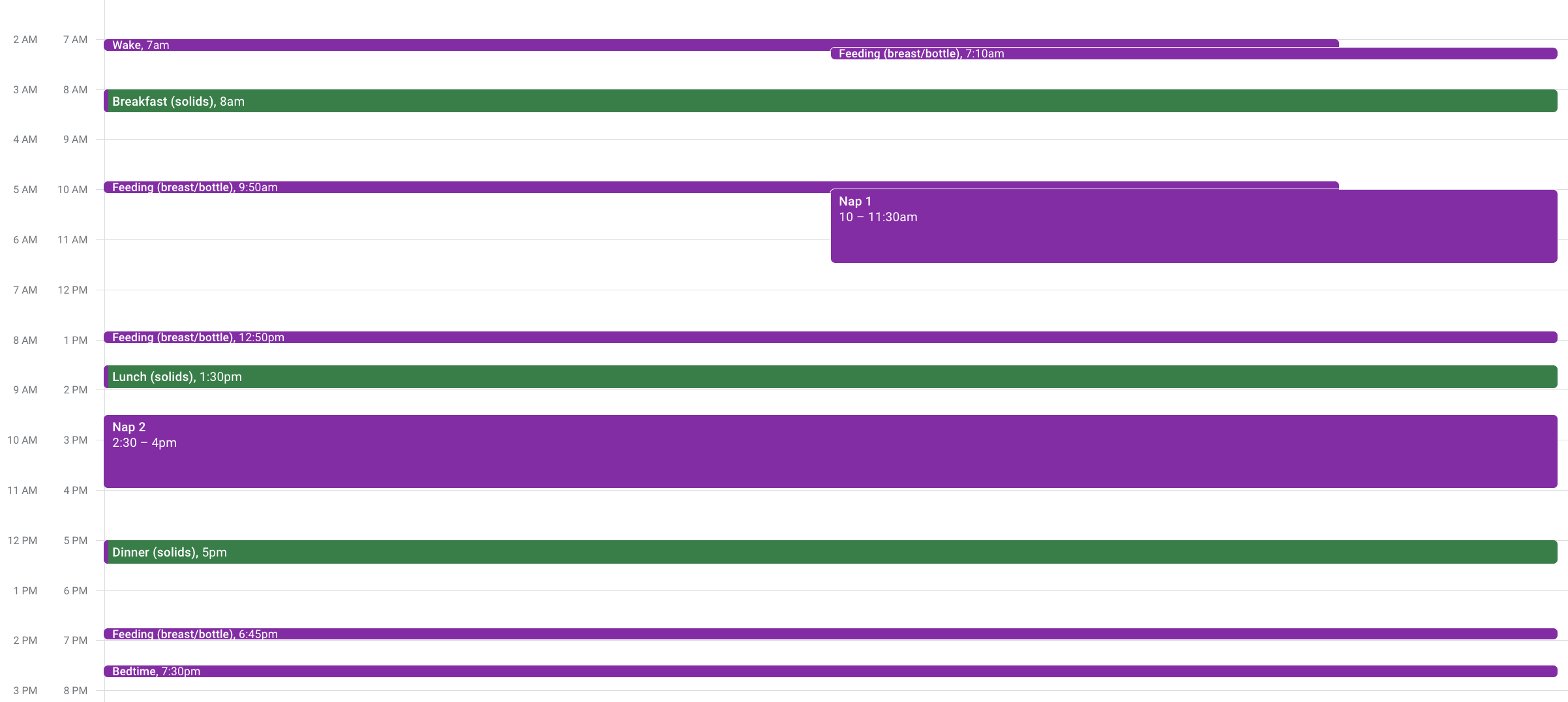

I also attached just a image of the data I wanted to use.

I followed up to add length as a parameter, add in a notes, and create another script to batch delete events.

3. Baseline Experience

The default experience is honestly excellent and doesn’t merit too much discussion. I’m starting to evaluate use cases on the same basis as other tech, but the highlights are:

- Faster than manual: Normally I’d include savings from future runs, but in this case I can say that Claude got the job done in parity or faster even on the first run.

- Silent errors: Zero. Once again, I spent my time iterating, not debugging code. And I found that Claude did what I told it to – I didn’t find any secret errors that meant I had to rethink the entire approach.

And here’s a calendar I produced, and the repo that created it:

Meandering

This experience has prompted me to think a little about calendaring, project management, and integrations, as they’re also pretty common activities in the workplace.

TL;DR: I think there’s a lot of untapped potential in using these AIs as project management tools – discovering, and in some cases, automating away risks. I think there’s probably a few techniques on the horizon that can make this possible. The capabilites of these AIs are truly bananas.

1. Asking for upfront risks and ambiguities [today]

Much like scoping any project, it’s sensible to think through edge cases, sources of error etc in order to make this load bearing. I asked Claude “what are the missing requirements and ambiguous statements in this request that might cause an issue?” and it gave me a suprisingly good list. Baking in this in as a first step in any request would be quite useful!

The request lacks specificity in several key areas: the time range and recurrence pattern for events, handling of conflicts and time zone changes, error management, user feedback mechanisms, event update processes, privacy settings, and notifications. It doesn’t address data validation, scalability for large numbers of events, long-term authentication management, or comprehensive logging and backup strategies. The absence of a defined testing approach is also notable. These ambiguities and missing requirements could lead to implementation challenges and potential reliability issues in real-world application of the script.

2. Learned tasks [soon]

Clearly Claude is good enough to operate my calendar, and it’s getting the code correct enough on first try that I believe it’ll do a good job. I’m going to use the word agentic here just for SEO.

That said, I’d love for it to be able to learn and save tasks for the future if it does a good job on the first ask. For example, after a successful run, I’d want it to ask “should I plan to do this in the future?” and be able to remember any modifications that it learned in the first go around. This behavior happens automatically at jobs (e.g. see one, do one, teach one) – I think it starts to feel like magic though when you don’t have to be very explicit about how to combine previously learned subtasks to get a bigger task done.

I also think tasks will benefit from being learned at the user (or at least group) level rather than globally – if there’s one thing I’ve learned from corporations, it’s that even simple processes are rarely consistent. For example, even if you scan inventory using the same tracking system in two different grocers, there’s almost always a different set of scanners, and different process for logging and checking that inventory, and differently configured software storing things.

Of course, learning one-shot and learning with even a few hundred aren’t the same thing – but being able to give structure to back and forth requests like the above that allows that sort of learning could help make this easier.

3. Automated change management [long-term]

In a past life I spent a load of time managing operational changes at companies with a lot of software and a lot of humans both experiencing and managing that change. I suspect however that that won’t look the same 10 years from now.

For example, let’s use an operational change in scanning bananas at a grocery store as a toy example:

- The main inventory system might count each banana individually, because there’s somehow there are people who really only want one banana.

- The procurement system, however, orders bunches of bananas, and assumes there are 5 bananas in a bunch, because there’s a supplier who sells bananas by the 5.

- A brilliant store manager realises that they don’t want packers in the store breaking down bunches of bananas only to have them go to waste.

- So the organisation decides to institute a “no banana left behind” policy, complete with engineering support to switch to a supplier who only sells single bananas.

In order to do this, the company decides it needs to shift banana tracking to a dedicated inventory system which will then sync to the main inventory system. In addition, associates will need retraining and new software to count singles, procurement will need to be changed for the new supplier, and the stores will need new inventory accuracy measurements to assure quality. But if it works, thousands of bananas will find a home so it’s obviously worth it.

This example might seem ludicrous, but I’ve seen very similar ones take months and months of eng work to then get close to launching, only to then experience delays because of a missed requirement like realising too late that the procurement system has to be able to place orders for both singles AND bunches of bananas at the same time, while still tracking a total banana count for accounting. On top of that, teams would be commissioned to create the solution evaluation, find the failure modes, engineer solutions, train associates, and then monitor performance.

Indeed, identifying risks in projects like these often requires figuring out what the fundamental differences in operations were first so you could plan for, manage, and communicate them – these were almost always double-edged swords where the operational reason the new software would be painful for the organisation to use was also the business reason that you were switching to it (e.g. selling single bananas is better for consumers but managing it is a pain).

Ideally, you’d want to ask questions like “which tasks won’t succeed”, “simulate where a given set of test cases fail and suggest what to do about it”. Unfortunately, the work involved in setting up the test cases meant the tests got done at the very end, and resulted in timelines getting pushed back for launcnhing the new software.

Building on #1 and #2 though, smart AIs, trained in how their companies operate, could run one-off simulations (re: integration tests) of the complex processes of those companies to find the failure points. While I think we’ve already priced in that AIs today can write the technical integration themselves, I’m more interested in the fact that they could also do the process integration: find the risks, making the important decisions, and writing the comms for the organisation.

In modern tech cos, there’s often an army of smart folks deployed to do this who could immediately go help make changes somewhere else. While changing processes constantly is in itself a defect (how many times have you changed the to do list software you use, only to get the same amount done), organisations tend to bias toward too much friction and too little ability to change. Excitingly, I suspect that perhaps we get to nimbler organisations, or smaller teams that can use AIs to bootstrap a lot of touchpoints that each end up costing money, or someone’s time.